Today was my last day in Bhadohi. A car came to pick me up from where I was staying at 10:30. I tossed my bags into the car and said goodbye to the people who had been hosting me. I told them each how much I had enjoyed staying at their home and finally getting to meet them. (These are the men who started and have been running Barakat’s Qazipur School over the past several years.) In their parting words, each of them said to me in almost exactly the same language something like this: “If I have used any unkind words, I am sorry. Forgive anything I might have said to upset you. I hope we are able to have a good relationship in the future and you are always welcome here.”

The similarity of their words made me think that it must be something everyone says when they say goodbye here if there have been disagreements. So of course, I said the same thing back to them, in somewhat different words. We had been discussing some matters over the past two weeks of how to run the schools, and we have not always seen eye to eye. Yet every night we ate together and joked together and learned more about each other–I found it quite refreshing to be able to be expressing our different views relating to one matter without feeling like anyone was holding it against anyone else.

Then before the car took off, one of them said, “Have you said goodbye to the children and teachers at the school?” I hadn’t. I hadn’t even thought of it. How rude.

“No. I should do that,” I said. So Amzad, who speaks quite good English and has been running the school for the past three years hopped in the car and told the driver to go to the school, and step on it! (It was in Hindi, so I’m just guessing at exactly what he said.)

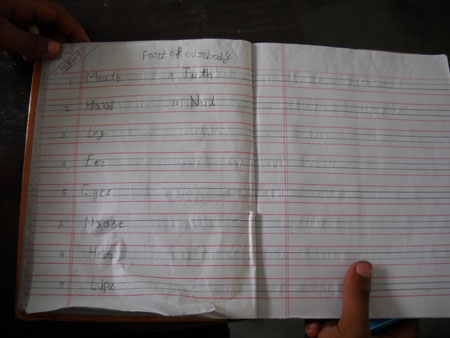

When we arrived at the school, classes were in session. I had hoped to catch everyone at their recess/lunch break so that I could address all the teachers and students at the same time. Instead I went into each of the seven classrooms and told them today was my last day in Bhadohi, I was heading back to the U.S., I had enjoyed meeting everyone and seeing how the school was being run. Finally I wished them all well for the year ahead and that I hoped I could come back at some point in the future.

For the younger children, Amzad translated. For the older kids, who have been studying English for a couple years, he thought it would be fun to see if any of them could understand what I was saying and explain it to the rest of the class. So for grades 3-5 I spoke more slowly and tried to use more simple words. One girl in 5th grade was actually able to get most of my meaning, which surprised and delighted me. Sometimes, it’s easy to lose track of the purpose of learning or to see the signs that it’s happening. And here was a student just 11 years old who had probably never heard any native English speaker talk before, and she could pick up what I was saying because she had studied English in school. Cool!

Another thing happened while I was in those classes saying goodbye. Speaking through a translator is a very different experience from speaking without one. You have to take breaks every few sentences for the person to translate. And that gives you time to reflect on what you want to say next, or to just space out if you already know what you’re going to say next. What I was saying was pretty simple, and I repeated it seven times, so I had plenty of time to look around the room at the children’s faces. As I was looking at them – some of their eyes fixed on Amzad as he was translating, some of them apparently captivated by me – I had a really weird feeling.

I felt like I was seeing the kids for the first time. Really seeing them. I had spent several hours in our two schools over the course of the past three weeks interviewing teachers, interviewing parents, interviewing students, talking to administrators, surveying the facilities, taking pictures, videotaping, asking all the questions I could think of. But somehow in all that time I hadn’t really taken time to just look at the kids and think about them. Who are they? What are they thinking? What are they feeling? Who are their friends?

It’s hard to explain how I was seeing them differently. All the rest of the time I had been so concerned with getting good pictures, or capturing the right moment on video, or trying to figure out the right question to get them to expose their true thoughts about going to school. I had been so focused on my objectives – my checklist of things I wanted to accomplish – that my mind was always there and not ever really processing what was in front of me.

It was only when I was ready to leave and had completed the checklist that my brain was free to see what was in front of me. At that moment, I felt a sense of awe. A sense that this is an incredibly important thing we are doing – helping to expand what is possible for these little people in the future. And it made me want to do whatever I could to make sure they have everything they need to make good lives for themselves.